Bruno Sammartino

| Bruno Sammartino | |

|---|---|

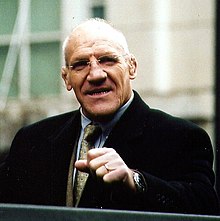

Sammartino as WWWF World Heavyweight Champion in 1971 | |

| Birth name | Bruno Leopoldo Francesco Sammartino |

| Born | October 6, 1935 Pizzoferrato, Abruzzo, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | April 18, 2018 (aged 82) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) |

Carol Sammartino

(m. 1959) |

| Children | 3; including David Sammartino |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Bruno Sammartino |

| Billed height | 5 ft 10 in (178 cm)[1] |

| Billed weight | 265 lb (120 kg)[1] |

| Billed from | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

| Trained by | Ace Freeman Rex Peery[3] |

| Debut | October 23, 1959 |

| Retired | August 19, 1987 |

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

Bruno Leopoldo Francesco Sammartino (October 6, 1935 – April 18, 2018) was an Italian-American professional wrestler. He is best known for his time with the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWF, now WWE). Sammartino's 2,803-day reign as WWF World Heavyweight Champion is the longest in the championship's history as well as the longest world title reign in WWE history.

Born in Italy to a family of seven, Sammartino grew up in poverty. As a child, Sammartino survived the German occupation of Italy during World War II. In 1950, he came to the United States with his family, where they would settle in Pittsburgh. Sammartino would later take up bodybuilding before beginning his career as a professional wrestler in 1959.

Dubbed "the Italian Strongman”[2] and "the Strongest Man in the World"[4] early in his career, Sammartino later earned the title "the Living Legend".[5] Known for his powerful bearhug[3][6] finishing move,[7] Sammartino wrestled for various territories in the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) before joining the WWWF territory.

Already recognized as a future star, Sammartino won the WWWF World Heavyweight Championship in 1963 after beating the inaugural champion, Buddy Rogers, in 48 seconds. He then held the title for a reign of a record 2,803 days – nearly 8 years. While doing so, Sammartino became a popular attraction in Madison Square Garden, selling out the arena numerous times throughout his career.[a] Sammartino would later reclaim the WWF Heavyweight Championship in 1973 for another reign of 1,237 days before gradually retiring from full-time competition.

After his retirement, Sammartino became a vocal critic of the drug use and raunchier storylines that became prevalent in the professional wrestling industry after his retirement but he reconciled with WWE in 2013 and headlined their Hall of Fame ceremony that year. Terry Funk commented that Sammartino "was bigger than wrestling itself".[8]

Early life

[edit]Bruno Leopoldo Francesco Sammartino was born in Pizzoferrato, Abruzzo, Italy, to Alfonso and Emilia Sammartino on October 6, 1935.[3][9] He was the youngest of seven children, four of whom died during his early childhood.[9] When he was four, his father immigrated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[9][10] During World War II, Pizzoferrato was invaded by troops of the Waffen SS, leading Emilia to hide Bruno and his siblings in a remote hideout at the top of a nearby mountain called Valla Rocca.[11][10] During this time, his mother would sneak into their German-occupied town for food and supplies.[10] In 1950,[12] she and the children joined her husband in Pittsburgh.[9]

When the Sammartinos arrived in the U.S., Bruno spoke no English and was sickly from the privations of the war years.[10] This made him an easy target for bullies at Schenley High School. He turned to weightlifting and wrestling to build himself up.[9] His devotion to weightlifting nearly resulted in a berth on the 1956 U.S. Olympic team, which went instead to eventual gold medalist Paul Anderson.[9]

In 1959, Sammartino set a world record in the bench press with a lift of 256 kilograms (565 lb), done without elbow or wrist wraps. When he brought the bar down, he did not bounce it off his chest, but set it there for two seconds before attempting the press.[6] He trained in wrestling with Rex Peery, the University of Pittsburgh team coach.[3]

He also became known for performing strongman stunts in the Pittsburgh area, and sportscaster Bob Prince put him on his television show. It was there that he was spotted by local professional wrestling promoter Rudy Miller, who recruited the young man into the ring.[3]

Professional wrestling career

[edit]Early years (1959–1963)

[edit]Sammartino made his professional debut in Pittsburgh on December 17, 1959, pinning Dmitri Grabowski in 19 seconds.[6] Sammartino's first match in Madison Square Garden in New York City was on January 2, 1960,[13] defeating Bull Curry in five minutes.[14]

Feeling like he was being held back in the New York territory in favor of National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) star Buddy Rogers, Sammartino gave his notice to Capitol Wrestling Corporation (CWC) owner Vince McMahon Sr. and planned to go to San Francisco to work for Roy Shire. While on his way to California, he missed two bookings in Baltimore and Chicago, and as a result was suspended in those territories. California honored the other state's suspension, leaving Sammartino out of work.[15] In his autobiography, Sammartino states that he believed McMahon set him up, by double-booking him and not informing him of his match in Baltimore, as a way of punishment.[16] Sammartino was forced to return to Pittsburgh and found work as a laborer.[15]

On the advice of wrestler Yukon Eric, Sammartino contacted Toronto promoter Frank Tunney hoping to take advantage of Toronto's large Italian population.[14] Sammartino made his Toronto debut in March 1962 and very quickly, with the help of self-promotion in local newspapers and radio programs, became an attraction. His ability to speak Italian also ingratiated him with that immigrant population.[15] With Whipper Billy Watson, Sammartino won his first professional wrestling championship in September 1962, the local version of the International Tag Team Championship.[17] Soon, he was in demand by other promoters in different Canadian territories.[15]

Sammartino also challenged NWA World Heavyweight Champion Lou Thesz twice for the championship in Canada. One match ended in a draw and the other with Thesz scoring a fluke pin after a collision, despite Sammartino controlling the 20 minute match from the beginning. This match was booked by NWA promoter Sam Muchnick as a preliminary to the forming of the WWWF, to ensure the dominance of the senior organization and its championship.[18]

World Wide Wrestling Federation/World Wrestling Federation (1963–1981)

[edit]First World Heavyweight Championship reign (1963–1971)

[edit]

After the first WWWF World Champion, Nature Boy Buddy Rogers, was hospitalized three times in April 1963 for chest pains, Vince McMahon Sr. and Toots Mondt made a command decision to make an emergency title switch. Between Antonino Rocca and Bruno Sammartino they went with the younger Sammartino who was 27 years old at the time. The match was scheduled to be concluded quickly so as not to risk Buddy's health any further. Promoters Mondt and McMahon Sr. cleared up Sammartino's suspension by paying his $500 fine, allowing him to return to wrestling in the United States. Sammartino won the title on May 17, 1963, defeating Rogers in 48 seconds.[19] Sammartino and Rogers faced each other two months later at Madison Square Garden in a tag team match, with Rogers and Johnny Barend defeating Sammartino and Bobo Brazil by 2 falls to 1. Rogers pinned Sammartino for the third and deciding fall. Rogers retired prior to their scheduled title rematch on October 4, 1963, in Jersey City, New Jersey's Roosevelt Stadium. Sammartino instead that night had his first match against new number one contender, Gorilla Monsoon. Because Monsoon won the match by disqualification, Sammartino retained his belt.

On December 8, 1969, he teamed with Tony Marino to win the WWF International Tag Team Championship by defeating The Rising Suns (Tanaka and Mitsu Arakawa). Company policy meant that Sammartino could not hold two championships simultaneously, so he was replaced by Victor Rivera.[20] Sammartino held the WWWF World Heavyweight Championship for seven years, eight months, and one day (2,803 days).[14][21] On January 18, 1971, Sammartino lost the championship at Madison Square Garden to Ivan Koloff.[22] Sammartino recalled the shocked silence that greeted the result, remarking he thought he had damaged his ears.[5] Later that year, he won the International Tag Team Championship for the second time by teaming with Dominic DeNucci.[20] Sammartino took a hiatus from the company in 1971 and 1972 working in Japan, and various territories.

Second World Heavyweight Championship reign (1972–1977)

[edit]

Later in 1972, Sammartino was asked back by McMahon Sr. to regain the title. After refusing McMahon Sr.'s initial offer, Sammartino was offered a percentage of all the gates when he wrestled and a decreased work schedule that only included major arenas. Soon after, Sammartino and then champion Pedro Morales teamed up for a series of tag team matches. In a televised match, Professor Toru Tanaka blinded both men with salt and they were maneuvered into fighting each other. When their eyes cleared, they kept fighting each other. Two weeks later, all syndicated wrestling shows in the WWWF showed a clip of Sammartino and Morales signing a contract for a title match at Shea Stadium. When McMahon Sr. gestured for them to shake hands, both wordlessly turned and walked away. On September 30, 1972, Sammartino and Morales wrestled to a 65-minute draw at Shea Stadium in New York.[23]

Eventually, on December 10, 1973, Sammartino regained the WWWF Heavyweight Championship by defeating Stan Stasiak.[5] During his second reign, on April 26, 1976, Sammartino suffered a legitimate neck fracture in a match against Stan Hansen at Madison Square Garden, when Hansen improperly executed a move and dropped Sammartino on his head.[9][14] After two months, Sammartino returned and faced Hansen in a rematch on June 25, 1976, at Shea Stadium, which was on the closed circuit TV undercard of the Ali vs. Antonio Inoki match for WWWF cities. The match was rated 1976 "Match of the Year" by Pro Wrestling Illustrated.[24]

In early 1977, Sammartino informed McMahon Sr. that he felt he could no longer continue as champion due to his injuries. On April 30, 1977, he was defeated by Superstar Billy Graham for the title.[5][25] His second title run lasted three years, four months, and twenty days (1,237 days).[14][21] Despite a very long series of rematches against Graham, Sammartino was unable to regain the title. His final attempt was in Philadelphia, just a few days before Graham was scheduled to lose the title to Bob Backlund.

Later career and initial retirement (1978–1981)

[edit]After his second reign ended, Sammartino leisurely toured the U.S. and the world. He wrestled then NWA World Heavyweight Champion Harley Race to a one-hour draw in St. Louis. He also wrestled and defeated Blackjack Mulligan, Lord Alfred Hayes, Dick Murdoch, Kenji Shibuya, and "Crippler" Ray Stevens. Also during this time, Sammartino began serving as color commentator for the WWF's syndicated programs, WWF Championship Wrestling and WWF All-Star Wrestling.

On January 22, 1980, his former student Larry Zbyszko turned on him at the World Wrestling Federation's Championship Wrestling show. Sammartino, shocked and hurt by Zbyszko's betrayal, vowed to make Zbyszko pay dearly. Their feud culminated on August 9, 1980, in front of 36,295 fans at Shea Stadium.[26] As the main event of 1980's Showdown at Shea, Sammartino defeated Zbyszko inside a steel cage.[26] In his autobiography, Hulk Hogan claimed that his match with André the Giant was the real reason for the huge draw at Shea Stadium; however, the feud between Sammartino and Zbyszko sold out everywhere in the build-up to the show. In contrast, Hogan and André headlined exactly one card in White Plains, New York before they wrestled at Shea, and they drew 1,200 in a building that held 3,500.[27]

Sammartino retired from North American wrestling full-time in 1981,[9] in a match that opened the Meadowlands Arena in East Rutherford, New Jersey. Sammartino pinned George "The Animal" Steele in his match. Sammartino then finished up his full-time career by touring Japan.

Return to the WWF (1984–1988)

[edit]

It was during this time Sammartino found out through Angelo Savoldi, a recently fired office employee of Capitol Wrestling Corporation, that he had been cheated by Vince McMahon Sr. on the promised gate percentages for his entire second title run. Sammartino filed suit against McMahon Sr. and his Capitol Wrestling Corporation.[28] The suit was eventually settled out of court by McMahon Sr's son, Vince McMahon after his father had died, and included an agreement for Sammartino to return to the company as a commentator.[21]

At the inaugural WrestleMania on March 31, 1985, Sammartino was in his son David's corner for his match against Brutus Beefcake.[29] The match ended in a double-disqualification after the Sammartinos began brawling with Beefcake and his manager Johnny Valiant. He returned to in-ring action soon after with his son, as they wrestled against Beefcake and Valiant at Madison Square Garden. The Sammartinos also teamed against "Mr. Wonderful" Paul Orndorff and Bobby "the Brain" Heenan in various arenas.[30]

Sammartino's highest-profile feud during this run was with "Macho Man" Randy Savage. An irate Sammartino attacked Savage during a TV interview, after Savage bragged about injuring Ricky Steamboat, by driving the timekeeper's bell into Steamboat's throat during a televised match. Sammartino defeated Savage in a lumberjack match for the WWE Intercontinental Heavyweight Championship via disqualification at the Boston Garden.[31] This allowed Savage to keep the championship, as titles cannot change hands via countout or disqualification. He was often teamed with Tito Santana and his old enemy George "the Animal" Steele (who was a fan favorite at this point in his career) to wrestle Savage and "Adorable" Adrian Adonis. The climax of their feud came was a victory for Sammartino and Santana in a steel cage match in Madison Square Garden. Sammartino also engaged in a feud with "Rowdy" Roddy Piper after Piper insulted his heritage on a segment of Piper's Pit at Madison Square Garden. Sammartino faced Piper in both singles and tag team matches. Sammartino teamed with Paul Orndorff in his matches against Piper, while Piper would tag with his "bodyguard", Ace "Cowboy" Bob Orton. Sammartino would eventually get the upper hand in the feud, by defeating Piper in a steel cage match at the Boston Garden. In 1986, Sammartino competed in a 20-man battle royal at WrestleMania 2 at the Rosemont Horizon in Chicago.[29]

Sammartino's final match was at a WWF house show in Baltimore on August 29, 1987, where he teamed up with Hulk Hogan to defeat King Kong Bundy and One Man Gang in the main event. Sammartino continued doing commentary on Superstars of Wrestling until March 1988.[17]

Non-wrestling roles and WWE Hall of Fame (1988–2018)

[edit]After leaving the WWE, Sammartino became an outspoken critic of the path on which Vincent K. McMahon had taken professional wrestling. He particularly criticized the use of steroids and "vulgar" storylines.[32][33][34] He appeared in the media in opposition to the WWE on such shows as The Phil Donahue Show, Geraldo, and CNN.[citation needed]

Sammartino worked as a commentator for the Universal Wrestling Federation. On October 28, 1989, Sammartino made a special appearance at the NWA pay-per-view event Halloween Havoc, where he was the special guest referee in a "Thunderdome" cage match which featured Ric Flair and Sting taking on Terry Funk and The Great Muta.[17] Sammartino worked several WCW events in a minor analysis role in the early 1990s, as well as a brief run doing color commentary with Jim Ross on Saturday Night in 1992. He also acted as special guest referee in World Championship Wrestling (WCW) for a series of matches between Flair and Randy Savage in June 1996.[17]

In 2006, he signed an independent deal with Jakks Pacific to produce an action figure, which is part of the WWE Classic Superstars line, Series 10.[35]

On March 25, 2010, Sammartino was honoured at the 74th annual Dapper Dan Dinner, a popular awards and charity fundraising event in Pittsburgh, with a lifetime achievement award, for which fellow former Studio Wrestling personalities Bill Cardille, "Jumping" Johnny DeFazio, Dominic DeNucci, Frank Durso, and referee Andy "Kid" DePaul were all present.[36]

In 2013, Sammartino accepted an invitation for induction into the WWE Hall of Fame, after having declined several times in prior years. He finally accepted the offer to join because he was satisfied with the way the company had addressed his concerns about rampant drug use as well as vulgarity.[37] The ceremony took place at Madison Square Garden on April 6, 2013, and Sammartino was inducted by Arnold Schwarzenegger.[38] Sammartino appeared on October 7, 2013, episode of Raw and received a birthday greeting in his hometown of Pittsburgh.[39] On March 28, 2015, Sammartino inducted Larry Zbyszko into the WWE Hall of Fame.[40]

Other media

[edit]Sammartino is included in two DVDs summarizing his career and life: Bruno Returns to Italy With Bruno Sammartino (2006) and Bruno Sammartino: Behind the Championship Belt (2006).[41][better source needed] Both were only released in Pittsburgh. Sammartino is honored on the Madison Square Garden Walk of Fame.[42]

Video games

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Legends of Wrestling II | Video game debut | [43] |

| 2004 | Showdown: Legends of Wrestling | [44] | |

| 2013 | WWE 2K14 | Downloadable content | [45] |

| 2023 | WWE 2K23 | [46] | |

| 2024 | WWE 2K24 | [47] |

Personal life

[edit]

Sammartino was married to his wife Carol from 1959 until his death in 2018. They had three sons together, David and fraternal twins Danny and Darryl. They were grandparents of four grandchildren. The Sammartinos lived in Ross Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania near Pittsburgh from 1965 on.[10] In 1998, he said he had been estranged from David since retiring from wrestling against David's wishes for a tag team.[48]

On April 6, 2013, Sammartino received the Key to the City in Jersey City, New Jersey.[49] May 17, 2013 was declared "Bruno Sammartino Day" in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. In 2013, Sammartino appeared as one of the Board of Governors in the nationally televised 69th Annual Columbus Day Parade.

Backstage incidents

[edit]In the late 1960s, Sammartino was involved in a fight with former Pennsylvania Athletic Commissioner Joe Cimino. Cimino was new to his post and intervened in a match finish involving Sammartino, who took a shot at Cimino in the ring and the argument continued backstage. Sammartino ended up in a screaming match with Cimino on Pittsburgh's local Studio Wrestling program, and Cimino suspended him for a month. Irvin Muchnick mentioned the incident in his book, Wrestling Babylon.[50]

In his autobiography, The Cowboy and the Cross: The Bill Watts Story: Rebellion, Wrestling and Redemption, Bill Watts told of witnessing a backstage incident between Sammartino and Gorilla Monsoon.[51] Watts wrote that Monsoon "soon found himself in deep water" when messing with Sammartino, and he did not go into further detail on the incident out of respect for Monsoon.[51]

On July 26, 2004, Sammartino and Ric Flair were involved in the "Who snubbed who?" non-confrontation at the Mellon Arena in Pittsburgh. Flair had denigrated Sammartino's wrestling ability in his book To Be the Man.[52] Flair said Sammartino refused to shake his hand at the event, while Sammartino said Flair saw him coming down the hall, turned, and rushed away.[52]

Death

[edit]Sammartino underwent heart surgery in 2011.[14] He died on April 18, 2018, at the age of 82 from multiple organ failure due to heart problems[11] following a two-month hospitalization.[53][54] WWE honored his life with a ten-bell salute before a house show in Cape Town, South Africa later that day, and again on the 23 April episode of Raw in St. Louis, Missouri.[55][56] Mayor Bill Peduto remembered him as "one of the greatest ambassadors the city of Pittsburgh ever had."[57]

Championships and accomplishments

[edit]

- George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2019 [58]

- Grand Prix Wrestling

- Grand Prix Tag Team Championship (1 time) with Edouard Carpentier

- International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2021[59]

- International Sports Hall of Fame

- Class of 2013[60]

- Keystone State Wrestling Alliance

- KSWA Hall of Fame (Class of 2012)[61]

- Maple Leaf Wrestling

- NWA Hollywood Wrestling

- Los Angeles Battle Royal (1972)[63]

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- Inspirational Wrestler of the Year (1976)[24]

- Match of the Year (1972) Battle royal[24]

- Match of the Year (1975) vs. Spiros Arion[24]

- Match of the Year (1976) vs. Stan Hansen[24]

- Match of the Year (1977) vs. Superstar Billy Graham[24]

- Match of the Year (1980) vs. Larry Zbyszko at Showdown at Shea[24]

- Stanley Weston Award (1981)[24]

- Wrestler of the Year (1974)[24]

- Ranked No. 200 of the top 500 singles wrestlers of the "PWI Years" in 2003[64]

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- Class of 2002[65]

- Sports Illustrated

- Ranked No. 10 of the 20 Greatest WWE Wrestlers Of All Time [66]

- World Wide Wrestling Alliance

- Hall of Fame (Class of 2008)[67]

- World Wide Wrestling Association

- WWWA World Heavyweight Championship (1 time, final)[68]

- WWWA World Tag Team Championship (1 time) with Argentina Apollo

- World Wide Wrestling Federation / WWE

- World Wrestling Association (Indianapolis)

- World Wrestling Council

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Feud of the Year (1980) vs. Larry Zbyszko[72]

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (Class of 1996)[73]

Notes

[edit]- ^ While Sammartino is commonly understood to have sold out Madison Square Garden 187 times, records indicate that he only did so approximately 45 times.

- ^ During Sammartino's second reign the title was known as WWWF Heavyweight Championship, due to the WWWF rejoining the National Wrestling Alliance.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Bruno Sammartino WWE profile". WWE.com. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Shields, Brian; Sullivan, Kevin (2012). WWE Encyclopedia: Updated & Expanded. DK. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-7566-9159-2.

- ^ a b c d e Hornbaker, Tim (2012). Legends of Pro Wrestling: 150 Years of Headlocks, Body Slams, and Piledrivers. Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1613210758.

- ^ Hornbaker, Tim (2015). Capitol Revolution: The Rise of the McMahon Wrestling Empire. ECW Press. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-1-77041-124-1.

- ^ a b c d e Schramm, Chris (September 15, 1999). "Sammartino the Living Legend". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on October 12, 2000. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c Davies, Ross (2001). Bruno Sammartino. Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-1435836259.

- ^ Murphy, Jan (October 1, 2014). "Jim Myers: The man behind the Animal". SLAM! Sports. Canoe.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Barrasso, Justin (April 18, 2018). "'The Joe DiMaggio of Professional Wrestling': Terry Funk Remembers Bruno Sammartino". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McFadden, Robert D. (April 18, 2018). "Bruno Sammartino, Durable Champ in WWE Hall of Fame, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Togneri, Chris (December 24, 2010). "Bruno Sammartino: Mountain of strength". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ^ a b Meltzer, Dave (April 26, 2018). "APRIL 30, 2018 WRESTLING OBSERVER NEWSLETTER: THE STORY OF BRUNO SAMMARTINO CONTINUED". Wrestling Observer. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Pro wrestling legend Bruno Sammartino dies at 82, Los Angeles Times, 18 April 2018

- ^ Hornbaker, Tim (2007). National Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly That Strangled Pro Wrestling. ECW Press. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-1-55022-741-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Oliver, Greg; Johnson, Steven (April 18, 2018). "Bruno Sammartino dies at 82". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Oliver, Greg (March 27, 2012). "Without Toronto, there would have been no Bruno Sammartino". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Sammartino, Bruno; Michelucci, Bob (1990). Bruno Sammartino: An Autobiography of Wrestling's Living Legend. Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-0911137149.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bruno Sammartino". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Meltzer, Dave (August 21, 1995). "history". Wrestling Observer Newsletter.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (2013). The History of Professional Wrestling: The Results WWE 1963–1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4928-2597-5.

- ^ a b c "10 championships you never knew existed in WWE". WWE. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Brian (April 18, 2018). "Remembering Bruno Sammartino, the singular face of a bygone pro wrestling era". CBS Sports. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (2013). The History of Professional Wrestling: The Results WWE 1963–1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4928-2597-5.

- ^ Davies, Ross (2001). Bruno Sammartino. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8239-3432-4. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "PWI Awards". Pro Wrestling Illustrated. Kappa Publishing Group. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (2013). The History of Professional Wrestling: The Results WWE 1963–1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-4928-2597-5.

- ^ a b Cawthon, Graham (2013). The History of Professional Wrestling: The Results WWF 1963–1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-4928-2597-5.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (2013). the History of Professional Wrestling Vol 1: WWE 1963–1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1492825975.

- ^ Bruno Sammartino v. Capitol Wrestling Corporation and Vince McMahon. Wrestlingperspective.com (26 August 1983). Retrieved on 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Professional wrestling great Bruno Sammartino dies at 82". The Times Herald. April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Cawthorn, Graham. "WWE in 1985". History of WWE. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (2013). The History of Professional Wrestling: The Results WWE 1963–1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 620. ISBN 978-1-4928-2597-5.

- ^ Molinaro, John (October 20, 1999). "Sammartino no fan of McMahon". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Mackinder, Matt (April 16, 2007). "Sammartino: McMahon is 'a sick-minded idiot'". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Muchnick, Irvin (March 20, 2013). "Bruno's bad call on WWE Hall of Fame shows Vince is right – everyone has a price". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ "Where legends are displayed". Classicfigs.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2008.

- ^ Dvorchak, Robert (March 26, 2010). "Dapper Dan: Malkin, Sammartino, Penn State volleyball claim awards". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ a b Robinson, Jon (February 3, 2013). "WWE to induct Bruno Sammartino into HOF". ESPN. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Caldwell, James (April 6, 2013). "WWE NEWS: Hall of Fame 2013 report - Complete "virtual-time" coverage of ceremony with Sammartino & Co., Stratus announces big news, Trump-McMahon?, more". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Caldwell, James (October 7, 2013). "CALDWELL'S WWE RAW RESULTS 10/7 (Hour 1): Battleground PPV fall-out, WWE Title match to continue at next PPV, one "firing", Bruno Sammartino, more". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ Caldwell, James (March 28, 2015). "WWE HALL OF FAME REPORT 3/28: Complete "virtual-time" coverage of 2015 Ceremony - Randy Savage inducted, Nash, Zbysko, Schwarzenegger, Flair, Michaels, more". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: In Memory For Bruno Sammartino - For The Fans (April 21, 2019). "Bruno Sammartino Behind The Championship Belt". Retrieved August 31, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ Satin, Ryan (April 19, 2018). "Madison Square Garden Pays Tribute To Bruno Sammartino". Pro Wrestling Sheet. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ Smith, David (December 2, 2002). "Legends of Wrestling II". IGN. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ Dunham, Jeremy (June 23, 2004). "Showdown: Legends of Wrestling". IGN. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ Kato, Matthew (January 7, 2014). "New WWE 2K14 DLC Introduces More Superstars". Game Informer. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ "WWE 2K23 Roster Official List | WWE 2K23". wwe.2k.com. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "WWE 2K24 Roster Official List | WWE 2K24". wwe.2k.com. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ Rouvalis, Cristina (October 28, 1998). "Wrestling with fame: Bruno Sammartino still a hero to fans". Post-gazette. Archived from the original on March 10, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- ^ Machcinski, Anthony J. (April 6, 2013). "Bruno Sammartino given key to Jersey City before his induction into WWE Hall of Fame". Jersey Journal. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Muchnick, Irvin (2011). Wrestling Babylon. New York: ECW Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-55022-761-1.

- ^ a b Watts, Bill (2006). The Cowboy and the Cross:The Bill Watts Story: Rebellion, Wrestling and Redemption. New York: ECW Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-55022-708-6.

- ^ a b Flair, Ric (2005). Ric Flair: to Be the Man. New York: Pocket Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-7434-9181-5.

- ^ ESPN.com Staff (April 18, 2018). "WWE Hall of Famer Bruno Sammartino dies at age 82". ESPN.com. United States: ESPN Inc. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ KDKA-TV Staff (April 18, 2018). "WWE Hall Of Famer Bruno Sammartino Dies At 82". KDKA-TV. Pittsburgh: CBS Corporation. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Alex (April 19, 2018). "Bruno Sammartino, wrestling's original good-guy hero, dies at 82". NBC News. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Hamlin, Jeff (April 23, 2018). "WWE Raw live results: Brock Lesnar returns to TV". Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ "Professional wrestling great Bruno Sammartino dies at 82". National Post. April 18, 2018.

- ^ "2019 TRAGOS/THESZ PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING HALL OF FAME CLASS ANNOUNCED - PWInsider.com". www.pwinsider.com.

- ^ "Induction Weekend 2022 | Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame".

- ^ Dr. Robert Goldman (March 12, 2013). "2013 International Sports Hall of Fame Inductees". www.sportshof.org. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Keystone Sate Wrestling Alliance - Hall of Fame". Keystone State Wrestling Alliance. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2006). Wrestling Title Histories (4th ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 978-0-9698161-5-7.

- ^ "Los Angeles Territory".

- ^ "PWI 500 of the PWI Years". Willy Wrestlefest. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Puskar, Gene J. (February 20, 2005). "Bruno Sammartino body slams hall of fame". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Pullar III, Sid (September 30, 2024). "20 Greatest WWE Wrestlers Of All Time". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ Rabito, Lou (November 6, 2008). "WWWA honors Bruno Sammartino, and vice versa". The Inquisitor. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ "World Wide Wrestling Association (1963)". Wrestling-Titles. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ "Triple H reveals Bruno Sammartino statue at WrestleMania Axxess".

- ^ "W.W.A. World Tag Team Title (Indianapolis)". Puroresu Dojo. 2003.

- ^ "WWC North American Heavyweight Title (Puerto Rico)". Wrestling-Titles.com.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated (PWI) 500 for 2007". Internet Wrestling Database. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ "Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame". Pro Wrestling Illustrated. Kappa Publishing Group. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Bruno Sammartino at IMDb

- Bruno Sammartino on WWE.com

- Bruno Sammartino at Find a Grave

- Bruno Sammartino's profile at Cagematch.net , Wrestlingdata.com , Internet Wrestling Database

- 1935 births

- 2018 deaths

- American male professional wrestlers

- American professional wrestlers of Italian descent

- Deaths from multiple organ failure

- Italian emigrants to the United States

- Italian male professional wrestlers

- Sportspeople from the Province of Chieti

- Professional wrestling announcers

- Professional wrestlers from Pennsylvania

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- American professional wrestling trainers

- Schenley High School alumni

- Professional wrestlers from Pittsburgh

- WWE Hall of Fame inductees

- WWE Champions

- Stampede Wrestling alumni

- 20th-century male professional wrestlers

- 20th-century American professional wrestlers

- NWA International Tag Team Champions (Toronto version)

- NWA United States Heavyweight Champions (Toronto version)

- People from Abruzzo

- People from Pittsburgh

- WWF International Tag Team Champions

- WWWF United States Tag Team Champions

- 20th-century Italian sportsmen