McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station | |

|---|---|

McMurdo Station from Observation Hill | |

Location of McMurdo Station in Antarctica | |

| Coordinates: 77°50′47″S 166°40′06″E / 77.846323°S 166.668235°E | |

| Country | |

| Location in Antarctica | Ross Island, Ross Dependency; claimed by New Zealand. |

| Administered by | United States Antarctic Program of the National Science Foundation |

| Established | 16 February 1956 |

| Named for | Archibald McMurdo |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Summer | 1,000 |

| • Winter | 153 |

| Winter: ~April to ~September | |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| UN/LOCODE | AQ MCM |

| Type | All year-round |

| Period | Annual |

| Status | Operational |

| Activities | List

|

| Facilities[2] | List

|

| Website | www.nsf.gov |

| Night and Day is seasonal, see Polar Night | |

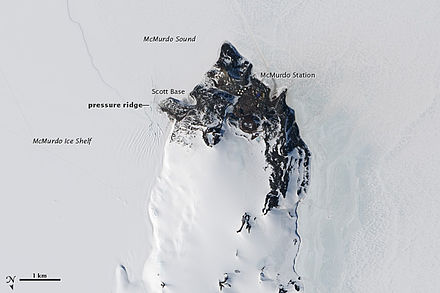

McMurdo Station is an American Antarctic research station on the southern tip of Ross Island. It is operated by the United States through the United States Antarctic Program (USAP), a branch of the National Science Foundation. The station is the largest community in Antarctica, capable of supporting up to 1,500 residents,[1][3] though the population fluctuates seasonally and during the antarctic night which has 24- hour darkness there is as little as a few hundred people. It serves as one of three year-round United States Antarctic science facilities. Personnel and cargo going to or coming from Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station usually first pass through McMurdo, either by flight or by the McMurdo to South Pole Traverse; it is a hub for activities and science projects in Antarctica. McMurdo, Amundsen-Scott, and Palmer are the three United States stations on the continent, though by the Antarctic Treaty System the bases are not a legal claim (though the right is not forfeited); they are dedicated to scientific research. New Zealand's Scott Base is nearby on Hut Peninsula and across the channel is a helicopter refueling station at Marble Point. The bases are served by airfields and a port, though access can be limited by weather conditions which can make it too hard to land aircraft, and an icebreaker may be needed to reach the port facility.

The base was first established in the mid-1950s as part of an international program to study and explore Antarctica for peaceful purposes. Daylight is seasonal at McMurdo corresponding to the south polar daytime, and the night, which is also winter, lasts from about April to September.

History

[edit]Name

[edit]

The station takes its name from its geographic location on McMurdo Sound, named after Lieutenant Archibald McMurdo of British ship HMS Terror. The Terror, commanded by Irish explorer Francis Crozier, along with expedition flagship Erebus under command of English Explorer James Clark Ross, first charted the area in 1841. The British explorer Robert Falcon Scott established a base camp close to this spot in 1902 and built a cabin there that was named Discovery Hut. It still stands as a historic monument near the water's edge on Hut Point at McMurdo Station. The volcanic rock of the site is the southernmost bare ground accessible by ship in the world. The United States officially opened its first station at McMurdo on February 16, 1956, as part of Operation Deep Freeze. The base, built by the U.S. Navy Seabees, was initially designated Naval Air Facility McMurdo. On November 28, 1957, Admiral George J. Dufek visited McMurdo with a U.S. congressional delegation for a change-of-command ceremony.[4]

International Geophysical Year

[edit]

McMurdo Station was the center of United States logistical operations during the International Geophysical Year,[4] an international scientific effort that lasted from July 1, 1957, to December 31, 1958. After the IGY, it became the center for US scientific as well as logistical activities in Antarctica. The IGY was international project in the late 1950s by 67 countries and involved over 4000 research stations Globally.[5]

The Antarctic Treaty, subsequently signed by over forty-five governments, regulates intergovernmental relations with respect to Antarctica and governs the conduct of daily life at McMurdo for United States Antarctic Program (USAP) participants. The Antarctic Treaty and related agreements, collectively called the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), opened for signature on December 1, 1959, and officially entered into force on June 23, 1961.

McMurdo was one of seven bases that the United States built for the IGY, which also included Hallett, Wilkes, Admundsen-Scott, Ellsworth, Byrd, and Little America.[6] Of these only McMurdo and Admundsen-Scott are still operated by the 21st century.[6]

As part of this endeavour, New Zealand was invited to build a base on Ross Island, and this lead to Scott base which went on to conduct many scientific projects. New Zealand was so impressed by the results of the studies it has supported Scott base ever since.[7]

The first scientific diving protocols were established before 1960 and the first diving operations were documented in November 1961.[8]

Nuclear power (1962–1972)

[edit]

On March 3, 1962, the U.S. Navy activated the PM-3A nuclear power plant at the station. The unit was prefabricated in modules to facilitate transport and assembly. Engineers designed the components to weigh no more than 30,000 pounds (14,000 kg) each and to measure no more than 8 feet 8 inches (2.64 m) by 8 feet 8 inches (2.64 m) by 30 feet (9.1 m). A single core no larger than an oil drum served as the heart of the nuclear reactor. These size and weight restrictions aimed to allow delivery of the reactor in an LC-130 Hercules aircraft, but the components were delivered by ship.[9]

The reactor generated 1.8 MW of electrical power[10] and reportedly replaced the need for 1,500 US gallons (5,700 L) of oil daily.[11] Engineers applied the reactor's power, for instance, in producing steam for the salt-water distillation plant. As a result of continuing safety issues (hairline cracks in the reactor and water leaks),[12][13] the U.S. Army Nuclear Power Program decommissioned the plant in 1972.[13]

Diesel generators

[edit]Conventional diesel generators replaced the nuclear power station, with several 500 kilowatts (670 hp) diesel generators in a central powerhouse providing electric power. A conventionally fueled water-desalination plant provided fresh water.[citation needed]

The base has six generators that can produce 900 kilowatts each, but it depends on the number of people at the base. With 800 people at the base around 1800 kilowatts are produced; the facility its not run at maximum capacity all the time. Heat from the engines, which have to be cooled regardless, is used to heat buildings at McMurdo by a heat exchanger. This design was completed in 1982.[14]

In 2011 a new generator system came online that had 3 in one building and two in another, the water plant building to provide redundancy. There are 4 engines rated at 1500 kW and one at 1300 kW, and power is also supplemented by the Wind power station at Scott base, which had reduces fuel consumption by tens of thousands of gallons at McMurdo.[15]

1962 Arcas rockets

[edit]Between 1962 and 1963, 28 Arcas sounding rockets were launched from McMurdo Station.[16]

McMurdo Station stands about two miles (3 km) from Scott Base, the New Zealand science station, and all of Ross Island lies within a sector claimed by New Zealand. Criticism has been leveled at the base regarding its construction projects, particularly the McMurdo-(Amundsen-Scott) South Pole highway.[17]

1998 Protocol on Environmental Protection

[edit]McMurdo Station has attempted to improve environmental management and waste removal in order to adhere to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, signed on October 4, 1991, which entered into force on January 14, 1998. This agreement prevents development and provides for the protection of the Antarctic environment through five specific annexes on marine pollution, fauna and flora, environmental impact assessments, waste management, and protected areas. It prohibits all activities relating to mineral resources except scientific ones. A new waste-treatment facility was built at McMurdo in 2003.

Scientific diving operations

[edit]

Scientific diving operations continue with 10,859 dives having been conducted under the ice from 1989 to 2006. A hyperbaric chamber is available for support of polar diving operations.[8]

21st century

[edit]

As of 2007[update], McMurdo Station was Antarctica's largest community and a functional, modern-day science station, including a harbor, three airfields[18] (two seasonal), a heliport and more than 100 buildings, including the Albert P. Crary Science and Engineering Center. The station is also home to the continent's two ATMs, both provided by Wells Fargo Bank. The work done at McMurdo Station primarily focuses on science, but most of the residents (approximately 1,000 in the summer and around 250 in the winter) are not scientists, but station personnel who provide support for operations, logistics, information technology, construction, and maintenance.

McMurdo Station briefly gained global notice when an anti-war protest took place on February 15, 2003. During the rally, about 50 scientists and station personnel gathered to protest against the coming invasion of Iraq by the United States. McMurdo Station was the only Antarctic location to hold such a rally.[19]

Scientists and other personnel at McMurdo are participants in the USAP, which coordinates research and operational support in the region. Werner Herzog's 2007 documentary Encounters at the End of the World reports on the life and culture of McMurdo Station from the point-of-view of residents. Anthony Powell's 2013 documentary Antarctica: A Year on Ice provides time-lapse photography of Antarctica intertwined with personal accounts from residents of McMurdo Station and of the adjacent Scott Base over the course of a year.

An annual sealift by cargo ships as part of Operation Deep Freeze delivers 8 million U.S. gallons (6.6 million imperial gallons/42 million liters) of fuel and 11 million pounds (5 million kg) of supplies and equipment for McMurdo residents.[20] The ships, operated by the U.S. Military Sealift Command, are crewed by civilian mariners. Cargo may range from mail, construction materials, trucks, tractors, dry and frozen food, to scientific instruments. U.S. Coast Guard icebreakers break a ship channel through ice-clogged McMurdo Sound in order for supply ships to reach Winter Quarters Bay at McMurdo. Additional supplies and personnel are flown into nearby Williams Field from Christchurch in New Zealand.

In 2016, scientist Dr David Hamilton died, when his snowmobile plunged into a crevasse about 25 miles (40 km) south of McMurdo in the shear zone (SZ). The ice is nearly 650 feet thick in this region, but crevasses can open as the ice moves, and the ice shelf was what Dr. Hamilton was studying at the time.[21] Hamilton was an experienced glaciologist, but there is many hazards to working in those conditions especially the crevasses.[22]

In 2017, the McMurdo Oceanographic Observatory (MOO) was installed underwater and removed in 2019; it provided underwater data and video from under the ice.[23]

In 2018, two people died while doing maintenance on fire suppression system in a generator building.[24][25]

In 2020, one large dormitory was demolished as part of a grand plan, however, the new dorm was never constructed and so in the 2020s McMurdo has had a self-made housing crisis leading to bottleneck that has lead to cancelled research projects.[26] At the start of 2020, Dorm 203 was torn down, but then development was halted because of the COVID-19 pandemic and several years later a new dorm was not built.[27] In the 2023–4 season, 67 of 137 projects were cut or scaled back due to housing issues.[26] In 2023, the NIH sent investigators to McMurdo in response to reports of sexual harassment and/or assault by men and women at the station.[28] One result of this was to ban the selling of alcohol at bars, though its not a blanket ban at the station.[29]

In 2024, the United States thanked the New Zealand Air Force, for conducted a difficult evacuation of a sick personnel from McMurdo during winter; this difficult flight takes place in total darkness, sub-freezing temperatures, and needs a "hot" refueling on the runway. The patient was successfully evacuated and achieved a stable condition. The roundtrip to New Zealand was a 7,500 kilometres (4,660 miles) flight[30]

Climate

[edit]With all months having an average temperature below freezing, McMurdo features a polar ice cap climate (Köppen EF). However, in the warmest months (December and January) the monthly average high temperature may occasionally rise above freezing. The place is protected from cold waves from the interior of Antarctica by the Transantarctic Mountains, so temperatures below −40° are rare, compared to more exposed places like Neumayer Station, which usually gets those temperatures a few times every year, often as early as May, and sometimes even as early as April, and very rarely above 0 °C. The highest temperature ever recorded at McMurdo was 10.8 °C on December 21, 1987. There is enough snowmelt in summer that a few species of moss and lichen can grow.

The station is a place where the Sun is continuously visible for about six months; then it is then continuously dark for the next six months, with a twilight, namely the equinoxes in between. These are, in observational terms, called one extremely long "day" and one equally long "night". During the six-month "day", the angle of elevation of the Sun above the horizon varies incrementally. The Sun reaches a rising position throughout the September equinox, and then it is apparent highest at the December solstice which is summer solstice for the south, setting on the March equinox.

The South Pole sees the Sun rise and set only once a year. Due to atmospheric refraction, these do not occur exactly on the September equinox and the March equinox, respectively: the Sun is above the horizon for four days longer at each equinox. The place has no solar time; there is no daily maximum or minimum solar height above the horizon. The station uses New Zealand time (UTC+12 during standard time and UTC+13 during daylight saving time) since all flights to McMurdo station depart from Christchurch and, therefore, all official travel from the pole goes through New Zealand.[31][32][33]

| Climate data for McMurdo Station (extremes 1956–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−20.4 (−4.7) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−19.4 (−2.9) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−21.3 (−6.3) |

−23.4 (−10.1) |

−26.5 (−15.7) |

−26.8 (−16.2) |

−28.4 (−19.1) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

−19.8 (−3.6) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−19.7 (−3.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.1 (−7.8) |

−25.0 (−13.0) |

−43.3 (−45.9) |

−41.9 (−43.4) |

−44.8 (−48.6) |

−43.9 (−47.0) |

−50.6 (−59.1) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

−45.1 (−49.2) |

−40.0 (−40.0) |

−28.5 (−19.3) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−50.6 (−59.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 16 (0.6) |

29 (1.1) |

15 (0.6) |

18 (0.7) |

21 (0.8) |

28 (1.1) |

17 (0.7) |

13 (0.5) |

10 (0.4) |

20 (0.8) |

12 (0.5) |

14 (0.6) |

213 (8.4) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 6.6 (2.6) |

22.4 (8.8) |

11.4 (4.5) |

12.7 (5.0) |

17.0 (6.7) |

17.8 (7.0) |

14.0 (5.5) |

6.6 (2.6) |

7.6 (3.0) |

13.5 (5.3) |

8.4 (3.3) |

10.4 (4.1) |

148.4 (58.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 2.6 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 46.1 |

| Average snowy days | 12.8 | 17.6 | 17.8 | 16.4 | 16.2 | 15.6 | 15.3 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 14.5 | 13.5 | 13.8 | 181.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.7 | 65.2 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 64.2 | 62.4 | 60.2 | 63.4 | 55.8 | 61.4 | 64.7 | 67.0 | 63.7 |

| Source 1: Deutscher Wetterdienst (average temperatures)[34] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation, snowy days, and humidity data 1961–1986),[35] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[36] | |||||||||||||

Communications

[edit]

Starting in 1963, McMurdo played host to one of the only two shortwave broadcast stations in Antarctica. From sign-on to 1971, the callsign was KMSA, from then on it was changed to WASA (W Antarctic Support Activities), later changing to AFAN in 1975. As KMSA, the station broadcast in the same building as the bowling alley, the barber shop and the retail store. A part of the vinyl collection reportedly came from Vietnam, believing to have been played by Adrian Cronauer's show in Saigon. In a 1997 interview to The Antarctic Sun, Cronauer denied these claims and the vinyl collection was apparently destroyed.[37] The station—AFAN McMurdo—initially operated on AM 600 and had a power of 50 W,[38] but by 1974, it transmitted with a power of 1 kilowatt on the shortwave frequency of 6,012 kHz and became a target for shortwave radio listening to hobbyists around the world because of its rarity. The station was picked up by DX for the first time in New Zealand in July 1974, and within a few months had its signal received as far as the US east coast. AFAN had changed frequencies several times in subsequent years.[39] The station continued broadcasting on shortwave into the 1980s when it dropped shortwave while continuing FM transmission.[40]

For a time, McMurdo had Antarctica's only television station, AFAN-TV, running vintage programs provided by the military. Broadcasts started on November 9, 1973, with a mix of US programs and interviews with visitors and scientists, as well as a daily news and weather service.[41] The station's equipment was susceptible to "electronic burping" from the diesel generators that provide electricity in the outpost. The station was profiled in a 1975 article in TV Guide magazine, where the station broadcast in the summer months, known by staff as "the season" (November to February), the only season where Antarctica was (at the time) open to aircraft.[42] In the mid-90s, a cable network was installed. By 1998, shortly after the launch of new AFN television services the year before, the traditional AFN network was broadcast over cable channel 2 (the channel that would soon become AFN Prime), NewSports (the current AFN News and AFN Sports) was on channel 11 and Spectrum (current AFN Spectrum) was on channel 13.[43] The cable network as of 2004 had six channels, with channel 13 generating occasional local content.[44]

McMurdo Station receives both Internet and voice communications by satellite communications via the Optus D1 satellite and relayed to Sydney, Australia.[45][46] A satellite dish at Black Island provides 20 Mbit/s Internet connectivity and voice communications. Voice communications are tied into the United States Antarctic Program headquarters in Centennial, Colorado, providing inbound and outbound calls to McMurdo from the US. Voice communications within the station are conducted via VHF radio.

Testing of the Starlink service began in September 2022,[47] with a second terminal providing connectivity for the Allan Hills field camp brought in November 2022.[48] The Starlink test ran from January to March of 2023, when it was shut off indefinitely to analyze test data.[failed verification]

Transport

[edit]

Three types of transport at McMurdo include land (ground), sea, and air. In each case the transport must contend with extreme cold, snow and ice. Access by sea might need an icebreaker, and ground transport may utilize snow tires, tracks, and sleds. Aircraft with skis may land on snow, such as the LC-130, while more prepared ice or compacted snow runways may tolerate conventional landing gear though extremely cold temperatures can complicate operating aircraft.

Ground

[edit]

A multitude of on- and off-road vehicles transport people and cargo around the station area, including Ivan the Terra Bus (a pun on Ivan the Terrible). Ivan the Terra is a snow coach that weighs 67,000 pounds empty and has been in service several decades.[49] The word Terra is the name of the snow bus made by the company Foremost, and this type of vehicle is also used in the Canadian arctic. It is an extreme-duty tri-axle bus with very large tires, and Ivan is powered by a 300 hp Cat engine, and it can normally transport 56 people at 25 mph. Despite its size, its very soft on the ground delivering only 15 psi of ground pressure.[50]

Ford E-Series Vans, modified for the conditions including a 20-speed transmission and snow tired, powered by a 7.3 Liter Turbodiesel V-8 is also used in both 4x4 and 6x6 versions.. One called the Ice Challenger set a land speed record to the pole in 70 hours.[51] Also Ford E-250 and 350 superduty trucks are used, and, again have to be modified and change is to put heaters on most components, and snow tired or track wheels. McMurdo operates about 60 superduty trucks in the 21st century.[52]

There is hundreds of vehicles at McMurdo, but also many different types: these fall into several categories based on where they are normally used. This include rock and/or ice road, local ice, traverse, ice edge, remote site, and inland station.[53] This includes vehicles like pickup trucks, M274 Mule utility truck, Tucker Sno-Cat (1700 series), Thiokol Sprytes, M51 Dump Truck, and Caterpillar bulldozers and loaders such as the D8, as well as other types such snowmobiles like the Bombardier Elan.[53][54] Sleds (aka Sledges) of various types and sizes have also been used, such as those pulled by a ski-do.[55][56][53]

There is a road from McMurdo to the New Zealand Scott Base, and open since 2005, an ice road and glacial traverse to the South Pole called the South Pole Traverse or McMurdo-South Pole highway.

The McMurdo-South Pole traverse, is a seasonal, over 1000 mile (1600 km) snow and ice road that crosses the frozen Ross Sea, glaciers, and the Antarctic ice cap to reach the South Pole. It was first opened at the end of 2005, though it must be maintained each year to check for new crevasses and clear new snow. It has reduced the number of flights to the South Pole, by enabling the bulk transport and fuel and cargo across the surface, and has also been used for adventuring records.[57]

Sea

[edit]

McMurdo has the world's most southerly harbor, this is important for bringing supplies to McMurdo and in support of projects in the Antarctic, but weather conditions necessitate an icebreaker.

McMurdo harbor has been opened by U.S. CGC Polar Star which comes every year to McMurdo. Access to ships in the harbor is can be done via an ice pier, though a modular causeway is in development.[58] Once the pass is open other types of ships can arrive include sealift, research, auxiliary vessels, and others bringing supplies and supporting research operations in Antarctica.[59]

Air

[edit]

McMurdo station is serviced seasonally from Christchurch Airport about 3,920 kilometres (2,440 mi) away by air,[60] with C-17 Globemaster and Lockheed LC-130, by two airports:

- Phoenix Airfield (ICAO: NZFX), a compacted snow runway which replaced Pegasus Field (ICAO: NZPG) in 2017

- Williams Field (ICAO: NZWD), a permanent snow runway for ski-equipped aircraft.

Also, there is a helicopter refueling station across the channel at Marble Point.[61] Historically, a seasonal Ice Runway (NZIR)[62] was used until December[63]though this has fallen out favor of the compacted snow runway of Phoenix airfield since 2017.[64]

In 2021-2 Operation Deep Freeze brought in 100 personnel and nearly 50 thousand pounds of food by air.[65]

Historic sites

[edit]

The Richard E. Byrd Historic Monument was erected at McMurdo in 1965. It includes a bronze bust on black marble, 150 cm × 60 cm (5 ft × 2 ft) square, on a wooden platform, bearing inscriptions describing the polar exploration achievements of Richard E. Byrd. It has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 54), following a proposal by the United States to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[66]

There is a memorial to Capt. Robert Falcon Scott and four others that died on their way back from the South Pole in 1912, that was erected in 1913 after they were found.[67] The Antarctic biologist and explorer Edward Wilson also died on that expedition.[68][67]

There is also a memorial to a construction worker, the U.S. Navy SeaBee Richard T. William, who died in 1956, when his bulldozer went through the ice: the memorial is statue of woman and called Our Lady of the Snows.[69]

The bronze Nuclear Power Plant Plaque is about 45 cm × 60 cm (18 in × 24 in) in size, and is secured to a large vertical rock halfway up the west side of Observation Hill, at the former site of the PM-3A nuclear power reactor at McMurdo Station. The inscription details the achievements of Antarctica's first nuclear power plant. It has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 85), following a proposal by the United States to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[66]

Nearby bases

[edit]

By road, McMurdo is 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from New Zealand's smaller Scott Base, which was built around the same time in the mid-1950s and the development of this area involved a collaboration between the United States and New Zealand; both were projects for the International Geophysical Year (IGY).[70][71] McMurdo and Scott base are technically in the New Zealand–claimed Ross Dependency on the shore of McMurdo Sound Antarctica, though by article IV of the 1961 Antarctic Treaty System the claim is in abeyance. The two bases were established to be close on purpose during Operation Deep Freeze in 1955+, which because of the IGY was part of a multinational project to establish bases in the antarctic, for which the sites were chosen. Christchurch International Airport in New Zealand, 3,920 kilometres (2,440 mi) to the north helps provide logistical support for flying in supplies for the bases. McMurdo has the southernmost harbor in the world, but for access by ships icebreakers can be needed to establish passage.

Three Enercon E-33 (330 kW each) wind turbines were deployed in 2009 to power McMurdo and New Zealand's Scott Base, reducing diesel consumption by 11% or 463,000 liters per year.[72][73] The subsequent failure of a proprietary, non-replaceable part critical to battery storage reduced the power generation of the turbines by 66% by 2019.[74] Three new wind turbines were planned for the 2023–4 season, with great capacity: one new one will be greater than previous three combined. The strong winds make wind power a practical alternative, and the new wind system should supply 90% of the power at Scott Base.[75]

Other stations near McMurdo, besides Scott Base, include the Italian seasonal base Zucchelli Station which is on the coast of the Ross Sea (Terra Nova Bay),[76] the German seasonal base Gondwana Station at Gerlache Inlet also in Terra Nova Bay,[77] and the South Korean Jang Bogo Station of South Korea also in Terra Nova Bay.[78]

Points of interest

[edit]

Facilities at the station include:

- Albert P. Crary Science and Engineering Center (CSEC)

- Chapel of the Snows Interdenominational Chapel

- Observation Hill

- Discovery Hut, built during Scott's 1901–1903 expedition

- Williams Field airport

- Memorial plaque to three airmen killed in 1946 while surveying the territory

- Ross Island Disc Golf Course[79]

Life

[edit]

Once a year around New Year's Day Icestock, the most southern music festival is organized, with performers being from the station and Scott Base.

There is an interfaith Church called the Chapel of the Snows, that hosts Protestant and Catholic services, as well as secular community organizations such as sobriety groups.[80]

There is a beerless bar at McMurdo, which is a noted social center of the station, and also a gym.[29][81] Although beer is no longer sold at the bar, a ration of alcohol is available to buy at the stationary store.[29]

The culture has been described as cross between a mining town and a NIH campus, or a summer camp with a lot work: working ten hour days six days a week is not uncommon. When downtime does come, and with internet access difficult, leisure time activities are popular such as ping-pong, art, and hiking for example.[82]

See also

[edit]- Air New Zealand Flight 901

- ANDRILL

- List of Antarctic field camps

- Byrd Station

- Castle Rock

- Crime in Antarctica

- Ellsworth Station

- Erebus crystal

- First women to fly to Antarctica

- Hallett Station

- List of Antarctic expeditions

- Little America (exploration base)

- Marble Point

- Palmer Station

- Plateau Station

- List of active permanent Antarctic research stations

- Ross Ice Shelf

- Siple Station

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Antarctic Station Catalogue (PDF) (catalogue). Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs. August 2017. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-473-40409-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "McMurdo Station". Geosciences: Polar Programs. National Science Foundation. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "4.0 Antarctica - Past and Present". National Science Foundation.

- ^ a b "US Antarctic Base Has Busy Day". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. November 29, 1957. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- ^ "International Geophysical Year (IGY)". Antarctic Heritage Trust. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "Celebrating the 65th anniversary of the International Geophysical Year | NSF - National Science Foundation". new.nsf.gov. July 1, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "International Geophysical Year (IGY)". Antarctic Heritage Trust. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Pollock, Neal W. (2007). "Scientific diving in Antarctica: history and current practice". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 37: 204–11. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ Rejcek, Peter (June 25, 2010). "Powerful reminder: Plaque dedicated to former McMurdo nuclear plant marks a significant moment in Antarctic history". The Antarctic Sun. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Priestly, Rebecca (January 7, 2012). "The wind turbines of Scott Base". The New Zealand Listener. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Clarke, Peter McFerrin (1966). On the ice. Burdette.

- ^ "Nuclear Science Abstracts". August 1967.

- ^ a b "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists". Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science. October 1978.

- ^ "McMurdo Power Station". www.coolantarctica.com. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Antarctic Sun: News about Antarctica - Full Power". antarcticsun.usap.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "McMurdo Station". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (January 24, 2003). "No, not a ski resort – it's the south pole". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Miguel Llanos (January 25, 2007). "Reflections from time on 'the Ice'". NBC News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- ^ "Protest photos". PunchDown. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Modern Marvels: Sub-Zero. The History Channel.

- ^ "U.S. Antarctic Program Investigator Perishes in Snowmobile Accident". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Coghlan, Andy. "Snowmobile plunge claims life of Antarctica researcher". New Scientist. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "About the Observatory, under the sea ice in Antarctica". MOO – Antarctica. Retrieved December 19, 2024.

- ^ "Two die at McMurdo".

- ^ McLaughlin, Eliott C. (December 12, 2018). "Technicians killed at Antarctica's McMurdo Station, foundation says". CNN. Retrieved December 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Kubny, Heiner. "Lacking beds in McMurdo leads to canceling research projects". Polarjournal. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "McMurdo, four years later – ANSMET, The Antarctic Search for Meteorites". December 11, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "https://www.npr.org/2023/11/03/1210418182/antarctica-sexual-harassment-national-science-foundation-investigation".

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c "At U.S. Antarctic base hit by harassment claims, workers are banned from buying alcohol at bars". PBS News. September 28, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Presse, AFP-Agence France. "US Praises New Zealand For 'World-class' Antarctic Rescue". www.barrons.com. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "What time zone is used in Antarctica?". Antarctica.uk. January 14, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Time Zones Currently Being Used in Antarctica". Time and Date AS. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ Dempsey, Caitlin (March 29, 2023). "Which Country Has the Most Time Zones?". Geography Realm. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Klimatafel von McMurdo (USA) / Antarktis" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ "McMurdo Sound Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ "Station McMurdo" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ "McMurdo radio station goes high-tech but retains retro vinyl collection" (February 24, 2012). Retrieved 2023-06-29

- ^ "Antarctic Radio Melts" (2012). Retrieved 2023-06-29

- ^ "American Forces Antarctic Network". Retrieved 2023-06-29

- ^ Berg, Jerome S. (October 24, 2008). Broadcasting on the Short Waves, 1945 to Today. McFarland. p. 213. ISBN 9780786451982 – via Google Books.

- ^ Antarctic Journal of the United States. January–February 1974. p. 29. ISBN 9780786451982 – via Google Books.

- ^ Shurkin, Joel N. (May 1975). They Usually Get a Rating of 40 (People, That Is)". TV Guide: 12-15.

- ^ "The Antarctic Sun" (PDF). February 7, 1998. p. 17. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ 2005 World Radio and Television Handbook, page 634

- ^ "Optus D1 satellite to provide critical link to Antarctica and to help monitor our changing Earth. " (September 20, 2007). Retrieved 2013-08-06

- ^ Wolejsza, C.; Whiteley, D.; Paciaroni, J. (2010)

- ^ Clark, Mitchell (September 15, 2022). "Starlink is even in Antarctica now". The Verge. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ Speck, Emilee (December 7, 2022). "Researchers studying oldest ice on Earth become first Antarctic field camp to use Starlink internet". FOX Weather. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "1 December 2018 Ground Transportation and Ivan the Terra-Bus! | PolarTREC". www.polartrec.com. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

- ^ McTaggart, Bryan (December 5, 2019). "BangShift-Approved Tour Bus: The Foremost Terra Bus...Nothing Will Stop This Monster!". BangShift.com. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

- ^ Tenson, Tijo (November 14, 2022). "This Is The Full Story Of Antarctica's Car Industry". HotCars. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Prosser, Richard (April 2, 2020). "Ford F-250 In Antarctica: The Super Duty On Ice". HotCars. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Blaisdell, George. (1991). Personnel and Cargo Transport in Antarctica: Analysis of Current U.S. Transport System. 70.

- ^ "The Antarctic Sun: News about Antarctica - Snowmobile Chopper". antarcticsun.usap.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Ski-doo and sledge McMurdo 1963". www.coolantarctica.com. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Bixby, William (1962). McMurdo, Antarctica. McKay.

- ^ "Icy Overland Trip May Add Ground Vehicles to South Pole Supply Missions". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

- ^ "Operation Deep Freeze: USCGC Polar Star Breaks Ice to Resupply McMurdo Station". DVIDS. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Operation Deep Freeze: USCGC Polar Star Breaks Ice to Resupply McMurdo Station". DVIDS. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Gateway to Antarctica". christchurchairport.co.nz. Christchurch Airport. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Marble Point Field Camp (WAP USA-28) – W.A.P." (in Italian). June 9, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "McMurdo Station Ice Runway - Antarctica". World Airport Codes. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ Blue-ice and snow runways, National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs. April 9, 1993.

- ^ "Aircraft Landing Areas". Archived from the original on September 19, 2018.

- ^ "Operation Deep Freeze begins at McMurdo Station". Pacific Air Forces. August 20, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "List of Historic Sites and Monuments approved by the ATCM (2012)" (PDF). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Magazine, Smithsonian. "Scott's Cross". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

- ^ "Edward Wilson". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

- ^ "Our Lady of the Snows | Glenn McClure". artforbrains.com/. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

- ^ "International Geophysical Year (IGY)". Antarctic Heritage Trust. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "Celebrating the 65th anniversary of the International Geophysical Year | NSF - National Science Foundation". new.nsf.gov. July 1, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "Ross Island Wind Energy". Antarcticanz.govt.nz. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ "New Zealand Wind Energy Association". Windenergy.org.nz. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ *Fernando, Maria (June 26, 2023). "Success Through International Collaboration in Microgrid Operation on Ross Island". youtube. Hotel Grand Chancellor, Hobart, NZ: Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

Maria Fernando is a Electrical & Wind Engineer at Antarctica New Zealand....In January 2010, the Crater Hill Wind Farm was commissioned and became operational, the world's southernmost wind farm. The three turbines, supply electricity to a shared power microgrid that connects Scott Base to McMurdo Station, called the Ross Island Energy Grid (RIEG). A number of improvements have been made over the lifetime of the RIEG, including automation of the Scott Base generators in order to more efficiently use generated electricity between the two stations when wind generated electricity is not enough to meet the power demands of the Ross Island network. Innovation and collaboration between Antarctica New Zealand and the United States Antarctic Program has made the project successful. Ongoing collaboration occurs to ensure the day-to-day operation of the microgrid and to work through any issues. This presentation will offer an update to the operation of the Crater Hill Wind Farm in the years since construction and the wider Ross Island Energy Grid, highlighting safety and maintenance issues that have occurred, lessons learned and successes achieved through collaboration.

- "20th COMNAP Symposium". COMNAP. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ "New turbines for the windiest continent". Antarctica New Zealand. Retrieved December 22, 2024.

- ^ "Mario Zucchelli Station, IT – POLARIN". Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "BGR - Logistics". www.bgr.bund.de. Archived from the original on April 23, 2024. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ Architects, Hugh Broughton. "Jang Bogo Korean Antarctic Research Station | Hugh Broughton Architects". hbarchitects.co.uk. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "Ross Island DGC". DGCourseReview. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- ^ "The Antarctic Sun: News about Antarctica - Building People Up at McMurdo's Chapel". antarcticsun.usap.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Antarctica Photo Library". photolibrary.usap.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Lee, Jack (January 7, 2020). "Practicing medicine in Antarctica: "It's a harsh continent"". Scope. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Clarke, Peter: On the Ice. Rand McNally & Company, 1966

- "Facts About the United States Antarctic Research Program". Division of Polar Programs, National Science Foundation; July 1982.

- Gillespie, Noel (November–December 1999). "'Deep Freeze': US Navy Operations in Antarctica 1955–1999, Part One". Air Enthusiast (84): 54–63. ISSN 0143-5450.

- United States Antarctic Research Program Calendar 1983